Carolina Coverfolk, Volume 3: Carolina Chocolate Drops

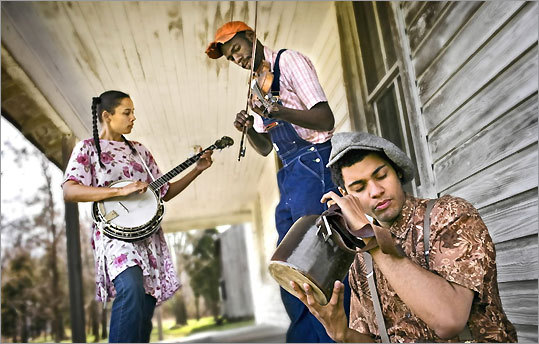

(An African American String Band recreates the Piedmont blues)

As noted previously (and as made obvious by the fact that this post is Volume 3 in a series), in recognition of our return to the Outer Banks for the fourth time since 2008, we’re in the midst of a set of Vacation Coverfolk features pulled from the archives of past trips to the North Carolina coast with a newly penned post on The Avett Brothers scheduled for the end of the week as a triumphant finale to our collected survey of music of, from, and about the region.

Earlier this week, Volumes 1 and 2 of our series took on songs whose titles mention the Carolinas, and a tribute to the songs of Elizabeth Cotten. Today, we present a slightly modified tripartite feature on the Carolina Chocolate Drops: a Carolina Coverfolk set originally posted in 2009, and postscripts from both a 2010 multi-artist feature that acknowledges their last album together before the original trio splintered off to become the quartet currently touring under the moniker, and a 2012 check-in which acknowledges the changes to personel and sound which resulted from that transformation.

APRIL 2009: There are two ways to learn music, really: by formal study and by direct transmission. The vast majority of musicians these days learn through the former method, a mixed bag of training, recorded music and noodling, balancing their books on a combination of heart and chords, songbook and soul.

APRIL 2009: There are two ways to learn music, really: by formal study and by direct transmission. The vast majority of musicians these days learn through the former method, a mixed bag of training, recorded music and noodling, balancing their books on a combination of heart and chords, songbook and soul.

There’s nothing wrong with this, per se: originality, after all, comes of such ownership, coupled with a sense of creation. Indeed, the folkworld thrives on such evolution, depending as it does on a connection to an everchanging culture. Those of us who love modern confessional and coffeehouse folk, not to mention the myriad hybrid forms which have emerged over the last few decades, appreciate the way music stretches and evolves in the hands of such practitioners.

But the transmissionary model isn’t dead. Just as there are audiophiles who insist on the scratchy authenticity of their original 78s, there are still folk musicians who believe that to truly become part of an authentic tradition of music, one must learn the trade authentically, too. From blueswoman Rory Block to Kentucky Appalachian Brett Ratliff, such modern followers of the folkways eschew records and scales, and look to the older ways, seeking out the ancient progenitors of their forms to listen and play along, learning the scratchy, earthy sounds and songs from their elders as if through osmosis.

The result isn’t generally polished, but that’s the point. Instead, such performers tend towards a raw sound, rich in feeling but often sparse in instrumentation, which favors emotional impact over consistent tempo. There’s no gloss here, only timelessness. And folk needs such old blood, too, lest it evolve so far it becomes unrecognizable; lest we lose touch with our origins, and forget that without the old ways to refer to, we cannot have them to reinvent.

Writ large, the Piedmont or “East Coast” blues emanates from a vast swath of rural East Coast America; popular in the early days of recorded music, from the twenties to the forties, its most famous tracks, such as Blind Boy Fuller’s 1940 recording of “Step It Up & Go”, sold as many as half a million copies to blacks and whites alike. Generally, the ragtime-based fingerpicking style which characterizes the once-popular African-American dance music is located as far North as Richmond, VA, and as far south as Atlanta, though of course the emergence of records helped spread the sound much farther in its heyday.

Writ large, the Piedmont or “East Coast” blues emanates from a vast swath of rural East Coast America; popular in the early days of recorded music, from the twenties to the forties, its most famous tracks, such as Blind Boy Fuller’s 1940 recording of “Step It Up & Go”, sold as many as half a million copies to blacks and whites alike. Generally, the ragtime-based fingerpicking style which characterizes the once-popular African-American dance music is located as far North as Richmond, VA, and as far south as Atlanta, though of course the emergence of records helped spread the sound much farther in its heyday.

The rediscovery of acoustic blues by folk fans in the sixties brought the music back into the mainstream, bringing many artists out of hiding and into the festival circuit, where they began to trade licks. Today, the Piedmont style and its repertoire can be found in the modern playing of many formally trained folk musicians, from Leo Kottke to Paul Simon.

Modern inheritors of the Piedmont sound, the founding members of “African American string band” Carolina Chocolate Drops may have found each other through the newest technology — two of the three met in a listserv and chatspace for Black banjo fans and players — but they picked up their music the old way, seeking out the oldest surviving members of the Piedmont style, learning at the feet of fellow North Carolinans Algia Mae Hinton and Etta Baker, who passed just before the ‘Drops released their debut albums Heritage and Dona Got A Ramblin’ Mind in 2007.

Modern inheritors of the Piedmont sound, the founding members of “African American string band” Carolina Chocolate Drops may have found each other through the newest technology — two of the three met in a listserv and chatspace for Black banjo fans and players — but they picked up their music the old way, seeking out the oldest surviving members of the Piedmont style, learning at the feet of fellow North Carolinans Algia Mae Hinton and Etta Baker, who passed just before the ‘Drops released their debut albums Heritage and Dona Got A Ramblin’ Mind in 2007.

Learning from North Carolina musicians magnifies the Carolinan connection in this particular incarnation. Fans of Baker, Hinton, and Carolina Chocolate Drops mentor Joe Thompson of Mebane, NC, said to be the last black traditional string band player, will hear the mannerisms of each in their playing. Even their name, which recalls that of 1920s fiddle-led band the Tennessee Chocolate Drops, pays tribute to the combination of form and geography.

Mountain strings — the banjo, guitar, and fiddle — feature heavily in the Piedmont sound, though not all at the same time; these, plus a smorgasbord of washboards, jugs, combs, and other household instruments round out the Carolina Chocolate Drops performance. But in the end, the instrumentation and the process are subservient to the madcap, heartfelt, almost desperately gleeful energy of the Piedmont style itself, as reincarnated here. It’s dance music, designed to get you jumping, appealing to your basest instincts, your wildest primal hopes and fears.

Here’s a short set of samplers — a modern cover done up old style, a video link to a great version of an old classic learned from Etta Baker, a handful of traditional tracks from their albums, soundtracks, and live appearances — which, in their timelessness and raw beauty, prove the value of the osmotic process, even as they celebrate the eternal spirit of the music itself.

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Tom Dula (trad.)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Starry Crown (trad.)

(from Dona Got a Ramblin’ Mind, 2007)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: I Got Blood In My Eyes For You (orig. Mississippi Sheiks)

(from The Great Debaters Soundtrack, 2007)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Cornbread and Butter Beans (trad.)

(from Heritage, 2007)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: In the Jailhouse Now (orig. Jimmie Rogers)

(live at the Old Town School of Folk Music, 2007)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Hit ‘em Up Style (orig. Blu Cantrell)

(live on WDVX Blue Plate Special, May 2008; video here, and worth it)

- VIDEO: Carolina Chocolate Drops: Goin’ Down That Road Feelin’ Bad (trad.)

(live from the Buckjump Blues Fest, 2006 — and plenty more where that came from!)

JANUARY 2010: I finally managed to catch the Carolina Chocolate Drops last weekend at the Somerville Theater, and was utterly thrilled to find they are even more stunning in concert than I had imagined. Their infectious joy in not just recovering but truly rejuvenating a whole set of found song, from old country blues and minstrel-show jazz to stringband and rural jugband classics, is evident in every smile, holler, and nuanced move on an array of authentic instruments, from quills and autoharp to banjo, fiddle, guitar, voice and bones. And as performers and ethnomusicologists, their patter and performance offers a first rate journey through the folk traditions of Black America.

JANUARY 2010: I finally managed to catch the Carolina Chocolate Drops last weekend at the Somerville Theater, and was utterly thrilled to find they are even more stunning in concert than I had imagined. Their infectious joy in not just recovering but truly rejuvenating a whole set of found song, from old country blues and minstrel-show jazz to stringband and rural jugband classics, is evident in every smile, holler, and nuanced move on an array of authentic instruments, from quills and autoharp to banjo, fiddle, guitar, voice and bones. And as performers and ethnomusicologists, their patter and performance offers a first rate journey through the folk traditions of Black America.

New album Genuine Negro Jig will include a studio version of their infamous Blu Cantrell cover and a delicious take on Tom Waits’ Trampled Rose alongside a whole new set of resurrected stringband and old-time jazz and blues tunes done in their inimitable Piedmont style. Here’s two delightful cuts from the newest – a tightened studio release of the aforementioned Blu Cantrell cover, and a sweet, wry newly-recorded version of old stringband classic Cornbread and Butterbeans – plus a Mississippi Sheiks cover from a recent tribute, and a live cut to keep your feet moving in the meantime; for more, order Genuine Negro Jig, sit back, and wait for the magic to arrive.

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Cornbread and Butterbeans (trad.)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Hit ‘Em Up Style (orig. Blu Cantrell)

(from Genuine Negro Jig, 2010)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Sitting On Top Of The World (orig. Mississippi Sheiks)

(from Things About Comin’ My Way: A Tribute to the Music of the Mississippi Sheiks, 2009)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: On The Road Again (trad.)

(live, via MySpace)

APRIL 2012: Unless you’ve been living under a cone of silence, you already know that once-featured, once-revisited African American String Band Carolina Chocolate Drops hit the ground this winter with a new release and a major change in personnel: gone is high-energy co-founder Justin Robinson, here to stay is beatboxer Adam Matta and new multi-instrumentalist Hubby Jenkins. The result, an appropriately titled mixed bag called Leaving Eden, underutilizes all members (Matta appears on just a small handful of tracks), leaving us hoping for a second round with more cohesiveness. But the album also continues the band’s journey aptly, bringing forth a broad tracklist of songs from spare to jubilant that channel the traditions of Appalachia, turning the folk of the slavefields and the holler (and their modern equivalents) into songs at once ancient and timeless. And though the set is somewhat ragged as it yaws from slave hollers and fiddle tunes to melodic folk narratives, some of the selections here are quite stunning, with these sparse yet vastly different covers of North Carolinian songwriter Laurelyn Dossett’s title track and South African guitarist Hannes Corteze’s instrumental Mahalla serving as an apt exhibit A and B, and a bonus track from the biggest Dylan tribute ever as further evidence.

APRIL 2012: Unless you’ve been living under a cone of silence, you already know that once-featured, once-revisited African American String Band Carolina Chocolate Drops hit the ground this winter with a new release and a major change in personnel: gone is high-energy co-founder Justin Robinson, here to stay is beatboxer Adam Matta and new multi-instrumentalist Hubby Jenkins. The result, an appropriately titled mixed bag called Leaving Eden, underutilizes all members (Matta appears on just a small handful of tracks), leaving us hoping for a second round with more cohesiveness. But the album also continues the band’s journey aptly, bringing forth a broad tracklist of songs from spare to jubilant that channel the traditions of Appalachia, turning the folk of the slavefields and the holler (and their modern equivalents) into songs at once ancient and timeless. And though the set is somewhat ragged as it yaws from slave hollers and fiddle tunes to melodic folk narratives, some of the selections here are quite stunning, with these sparse yet vastly different covers of North Carolinian songwriter Laurelyn Dossett’s title track and South African guitarist Hannes Corteze’s instrumental Mahalla serving as an apt exhibit A and B, and a bonus track from the biggest Dylan tribute ever as further evidence.

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Leaving Eden (orig. Laurelyn Dossett)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Mahalla (orig. Hannes Corteze)

(from Leaving Eden, 2012)

- Carolina Chocolate Drops: Political Words (orig. Bob Dylan)

(from Chimes of Freedom: The Songs of Bob Dylan, 2012)

Like what you hear? Carolina Chocolate Drops will be appearing at several folk festivals this summer, but there’s more than one way to support the old ways; musicians can’t survive without fans who buy records, and the Carolina Chocolate Drops catalog is well worth owning. Buy direct from the artists, or head out to your local record store; both strategies help spread the word and warm the heart while keeping music small and local.

And stay tuned this week for more Carolina Coverfolk, including features on James Taylor and The Avett Brothers!

Category: Carolina Chocolate Drops, Reposts, Vacation Coverfolk 2 comments »

September 9th, 2013 at 9:24 pm

[…] we pulled from the archives to bring you features on the songs and coverage of Elizabeth Cotten, Carolina Chocolate Drops, and Doc Watson, and a mixtape of coverfolk songs with Carolina in the […]

April 22nd, 2015 at 2:36 pm

[…] Volume 3: Carolina Chocolate Drops (An African American String Band Recreates the Piedmont Blues) […]