After two weeks preparing to teach a 10th grade English class in the struggling urban school where I work, at the eleventh hour, I’ve been re-assigned to teach English to a cohort of students who failed 9th grade English last year.

The class is bigger than any I have taught at this school – too big, as it stands, for the tables, chairs, and computer stations – and these are not students who share. Class starts Monday. And though I am generally fearless, the task before us is daunting, indeed.

As I noted in February of 2012, in a feature which I have reposted below, the challenges we face in inner-city schools are myriad – a complex of environmental, situational, and institutional issues. But this particular group is an extreme among extremes. Many of these students do not speak English at home; parent contact information is universally absent or out of date. Most only come to class once or twice a week, and are aggressive, sullen, and highly disruptive when they do. And though it is hard to benchmark, given their chronic absences and refusal to work, their test scores suggest that their skills are years below grade level.

In short: these students see school not as meaningless, but as a constant and powerful aggressor. They share a perception of literature as both alien and enemy. And I know all this intimately, because the majority of the students in this class failed my 9th grade seminar last year, too, which stacks the deck against establishing a healthy classroom relationship among us.

It is not in me to plan for failure. I am a good teacher, damn it: creative, relentless, hopeful, and engaging. I know that there is work to be done here, and that miracles can be made. But getting it right will require a long high wire act, with no net.

In order to accommodate this unexpected opportunity, Cover Lay Down will be on hiatus for a week or two until I regain my footing in the classroom. I regret the necessity, but trust that regular readers, and the artistic community we work to support, will understand.

Thanks to all, in advance, for allowing me this chance to do right by my students.

Originally posted February, 2012

Student grades are due tomorrow, but we went to church anyway – we had to sing, and after two years of semi-regular practice as a Unitarian Universalist, I have come to a place in my life where I find peace and solace in shared practice which starts and ends with love and service, togetherness and open-ended truths, and a shared commitment to social justice.

Much of this is due to the particulars of our chosen worship setting. The UU church which we attend is in transition, with an interim minister who has my undying respect; wise, and gentle, with a knack for bringing new texts and ideas to the table, presenting them clearly and coherently, and then braiding them together to reveal the thing which we needed most of the world in that moment.

I experience her sermons as a kind of miracle of the mind, that binds my soul and body, and answers my unspoken need. Even when I am distracted by my own thoughts, her bright, intelligent prompting provides an avenue for me to come to myself with new eyes, and with a renewed determination to accept that which has been lurking in my heart and mind.

And in this case, a sermon on blessings and failures, and how we so often fail to allow ourselves to experience the joys and sadness they should bring us, has brought me back to my students.

The students I teach are ill-prepared for success. They are the product of a city that is stacked against them, a community that is in too much of a hurry to address the deep foundation issues which would support true progress, a system that is under too much pressure to make it look like things are working. They come to my ninth grade classroom with fifth grade reading skills, without the stamina to be learners for more than a few minutes per class day, with anger against me for enforcing the most basic rules, and an image of the classroom as a competitive space, where they win if they can overwhelm the lesson, or if they can sleep successfully, and thus avoid confronting their unpreparedness.

The students I teach are ill-prepared for success. They are the product of a city that is stacked against them, a community that is in too much of a hurry to address the deep foundation issues which would support true progress, a system that is under too much pressure to make it look like things are working. They come to my ninth grade classroom with fifth grade reading skills, without the stamina to be learners for more than a few minutes per class day, with anger against me for enforcing the most basic rules, and an image of the classroom as a competitive space, where they win if they can overwhelm the lesson, or if they can sleep successfully, and thus avoid confronting their unpreparedness.

They also come, if indeed they come at all – one in five students is absent on a given day – with long histories of pitting themselves against the world, which make them almost unteachable for most of the semester, until and if we can delay the curriculum long enough to get into their hearts. Most of them are incapable of experiencing joy or sadness at all, let alone the empathy we assume is prerequisite for understanding a text. Instead, they experience only despair and bitterness, disappointment and pride – emotions they cannot acknowledge, to themselves or others, lest they appear weak, and lose the only game they know.

A few of them manage to survive and move forward, and a tiny, tiny percentage aim to thrive. But these are the minority: just 25% of students in the city where I teach even graduate from high school within four years, and it’s not hard to see why. Last week, a boy in one of my classes taunted a girl into attacking him; in the aftermath, his lack of ownership in instigating the fight was both frustrating and expected, but it was his comment that “It wasn’t a fight; she’s a girl” that reminded me just how unprepared these almost-men and almost-women are to accept even the basic conditions that we believe are necessary to help them move forward.

We do what we can for them, and sometimes more than we can afford, in an environment where each student gets just two minutes of my individual attention, if that, per day. In tiny slices of time we struggle to push our way in, to learn who they are as individuals, to identify the gaps between where they are and where the curriculum assumes they are, and construct a pathway for them that bridges their particular chasm.

But half a bridge is no better than none, and it may be worse, given that it contains so much false hope. In the end, it is our lot to hold them responsible for their actions, lest we become part of the machine that lies to them, and tells them that they are ready. It hurts to fail so many, but it would hurt more to pass them along without merit or ability, to undermine their next classes, to perpetuate the lie that a good heart, however buried and patinaed, is evidence of success.

And so many fail. Despite unanswered parent phone calls and teacher conferences full of hopelessness, long unattended after school sessions offered, a hundred new attempts at kind words and coaxing, over half of the 80 final grades I will enter into the database before the sun rises tomorrow are F’s. Of the remainder, another half are within the D range, marking their recipients as desperately unprepared academically but willing to struggle just enough to produce something that hints of promise, though probability says that not one of these 20-or-so students will pass sufficient classes this year to move on, leaving them stuck in the eternal-seeming limbo that is another ninth grade year.

Only four of my students from last term earned an A of any sort. Only six earned B’s. And of those, there are still one or two who only bothered and blossomed in my class, or perhaps one other – they liked me, but in a manner untranslatable to other teachers’ style.

How did we get from sermon to city? These things are related, somehow, though they are hard to untangle. But today, in church, as the minister read a section from Everything I Need To Know I Learned In Kindergarten, I was reminded that my students do not know what we taught them then, if indeed we taught them at all.

And although the time for sharing had passed, suddenly, in the middle of the sermon, I wanted to say a prayer for my students.

I wanted to light a candle for my beloved failures, curled up against the world so tightly that, like fists, all they can do is destroy.

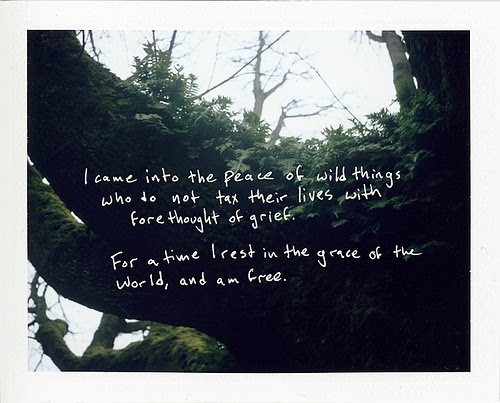

I wanted to cry, and ask forgiveness; to say that I really did do everything there is to do, and let the feelings simply be, in the community I trust, even as I despair in the peace of my beloved wild things, who tear at me until the bell rings, and the clock runs out, and it is too late.

I wanted to, but I didn’t.

I offer it here, instead.

I talk a good game in the hallways about how the new evaluation tool we use in my district: about how the tool is sound, but an inconsistent and aggressively biased application of it is a major focal point of the terror and frustration we feel as teachers. But it is also true that the threat of observation can prompt a healthy, deliberate attention to detail and self-reflection, a sort of critical, vocational soul searching which, when it works, can push us to be our best. It is a social scientist’s Heisenberg principle, in which the act of being observed changes the subject, using pressure to turn coal into diamond.

I talk a good game in the hallways about how the new evaluation tool we use in my district: about how the tool is sound, but an inconsistent and aggressively biased application of it is a major focal point of the terror and frustration we feel as teachers. But it is also true that the threat of observation can prompt a healthy, deliberate attention to detail and self-reflection, a sort of critical, vocational soul searching which, when it works, can push us to be our best. It is a social scientist’s Heisenberg principle, in which the act of being observed changes the subject, using pressure to turn coal into diamond.  As always, steeping too long in work has left me in too deep to move on quickly. My head swims still with questions, because of how deeply we considered them in our poems and analyses, because we were able to come to the higher order ones together. And I find myself pondering the world, and my place in it, after a day where everything went right, in a place where for so long I have been neither free nor safe.

As always, steeping too long in work has left me in too deep to move on quickly. My head swims still with questions, because of how deeply we considered them in our poems and analyses, because we were able to come to the higher order ones together. And I find myself pondering the world, and my place in it, after a day where everything went right, in a place where for so long I have been neither free nor safe.

The students I teach are ill-prepared for success. They are the product of a city that is stacked against them, a community that is in too much of a hurry to address the deep foundation issues which would support true progress, a system that is under too much pressure to make it look like things are working. They come to my ninth grade classroom with fifth grade reading skills, without the stamina to be learners for more than a few minutes per class day, with anger against me for enforcing the most basic rules, and an image of the classroom as a competitive space, where they win if they can overwhelm the lesson, or if they can sleep successfully, and thus avoid confronting their unpreparedness.

The students I teach are ill-prepared for success. They are the product of a city that is stacked against them, a community that is in too much of a hurry to address the deep foundation issues which would support true progress, a system that is under too much pressure to make it look like things are working. They come to my ninth grade classroom with fifth grade reading skills, without the stamina to be learners for more than a few minutes per class day, with anger against me for enforcing the most basic rules, and an image of the classroom as a competitive space, where they win if they can overwhelm the lesson, or if they can sleep successfully, and thus avoid confronting their unpreparedness.