Vacation Coverfolk: On the Trail of Social Justice

(songs of place and protest from Montgomery to Memphis)

Yes, it’s been a while since we turned up here, and there’s much to celebrate as we slowly return to the mailbag of the last two months, including transformative re-recordings from new artists and well-loved voices, crowdfunded campaign-driven albums promising the best of honest folk and acoustic coverage, tributes to the dearly departed, and more.

If I have been busy elsewhere, it is due in no small part to a growing mindfulness as I renew my commitment to the work of worldchanging, in my increasingly intertwined roles as a practitioner and worship leader in an engaged Unitarian Universalist congregation on one hand, and as an English teacher in a Title 1 urban high school on the other. And although the prompt to travel originally came through my spouse, who was looking for some company and an adventure on the way back from an equally transformative conference, it is this twinned sense of connection to the world around me – the vocational and the spiritual; the service and the service – that brought me to and through the last week, sustaining me deeply in mind and spirit as we traveled North from Louisiana, with stops at a series of sites and settings essential to the long struggle for all Americans to be and feel safe, free, and able to access the world-as-it-should-be.

So join us today as we dip into the experience in literary slideshow, with a set of covers tender and torn in their address of the pliancies and pilgrims of social justice work in our beloved nation. And then stay tuned, as the summer surrounds us, and the waters of music flow like the Mississippi, strengthening and serving our hearts and our minds alike.

Lights dim and the landing gear rises on the plane to New Orleans. People all around me turn pages and flip screens, and it occurs to me that that I am both gladdened and saddened by the realization that planes represent a concentration of literacy, given how much the picture depends on affluence, and reinforces long-distance travel as a privilege unavailable to my rising 11th graders and their peers. Me, I’m reading James McBride’s The Color Of Water, in preparation for teaching it in the fall: making notes in the margins and savoring the internal dialogue of reader and text as McBride alternately confronts the nuances of growing up black with a mother who hid her history of whiteness in a veneer of standoffishness, and dances around those images, providing powerful nuance to the national dialogue of race, belief, and identity through character and connotation.

Lights dim and the landing gear rises on the plane to New Orleans. People all around me turn pages and flip screens, and it occurs to me that that I am both gladdened and saddened by the realization that planes represent a concentration of literacy, given how much the picture depends on affluence, and reinforces long-distance travel as a privilege unavailable to my rising 11th graders and their peers. Me, I’m reading James McBride’s The Color Of Water, in preparation for teaching it in the fall: making notes in the margins and savoring the internal dialogue of reader and text as McBride alternately confronts the nuances of growing up black with a mother who hid her history of whiteness in a veneer of standoffishness, and dances around those images, providing powerful nuance to the national dialogue of race, belief, and identity through character and connotation.

Reading slowly, savoring moment and meaning, is not all that natural to me; generally, I read for pleasure, voraciously, and am known to finish a book in an evening. But we are here, my wife and I, on a pilgrimage. Our aim is to meet up in the South to discover this dialogue together after an exhausting school year, driving slowly through the history of the social justice movement in America, with planned stops in Selma, Montgomery, Birmingham, Memphis, and at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati before heading homeward to recover our children. And, in the end, my reading, deeply thought-provoking and grounding, still mostly unfinished, makes a perfect metaphor for the experience that followed.

We start, fittingly, on Sunday, at the morning service for this year’s Unitarian Universalist General Assembly, which my wife has been attending in her role as Director of Religious Ed for our beloved UU congregation in Springfield, MA. The hall is vast, and the clarion call clear: ours is a spiritual path that calls us to love and action, continuing the good work of commitment and dialogue in service to attaining global justice in many areas, from ecology to economics, with race, gender, and class consciousness at the forefront. The service includes a reading of Naomi Shihab Nye’s Gate A-4, a powerful poem of hope and immigrant identity, which I taught last year; mention is made of two men whose sexuality is both irrelevant and noteworthy, IT professionals who serve the UU community, who were attacked the previous night in the French Quarter. The collection plate goes to Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, an organization working to challenge and change the school-to-prison pipeline that plagues our inner cities. We give what we can, and sing with tears in our eyes the hymns of commitment and claim amidst thousands.

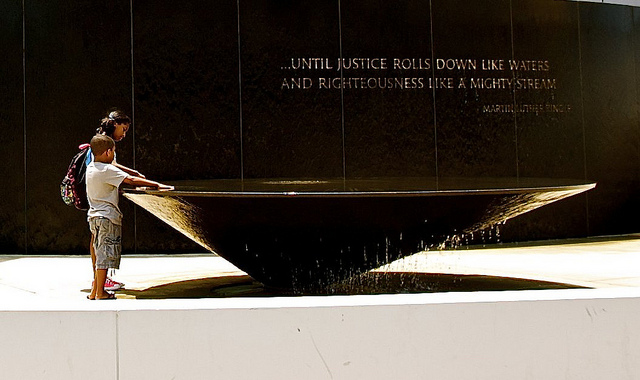

From there to Montgomery, Alabama, where Maya Lin’s Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial fountain is a UU chalice in the afternoon sun at the foot of the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the giant footsteps in the crosswalk which mark the approach to the statehouse steps loom large as history in front of the Baptist church where King and others led the charge for justice. It is quiet here, being Sunday, and quieter still as we drive in reverse the long march path to Selma, where much of the town is boarded up and broken, reminding us that no matter how far we have come forward since black leaders and their white allies crossed the bridge into violence and chaos, we still have a long way to go.

The next day, Birmingham, where the streets radiate out from a once-bombed church and Kelly Ingram Park, a one-time central staging ground for protest and now a well-curated space featuring statues of children huddling before firehoses and snarling dogs. We walk the Birmingham Civil Rights Heritage Trail in the morning heat, tracing the original paths of marches on power both government and retail, making our slow and pensive way through sidewalks lined with plaques and textbook-familiar photographs, experiencing the expected temporal tension as 1963 comes to us superimposed over a shaded modern reality. Back in the park, a homeless woman named Beatrice, who hugged me earlier for offering her two cigarettes instead of one, sings hymns heartily into the morning air as we take our leave.

The next day, Birmingham, where the streets radiate out from a once-bombed church and Kelly Ingram Park, a one-time central staging ground for protest and now a well-curated space featuring statues of children huddling before firehoses and snarling dogs. We walk the Birmingham Civil Rights Heritage Trail in the morning heat, tracing the original paths of marches on power both government and retail, making our slow and pensive way through sidewalks lined with plaques and textbook-familiar photographs, experiencing the expected temporal tension as 1963 comes to us superimposed over a shaded modern reality. Back in the park, a homeless woman named Beatrice, who hugged me earlier for offering her two cigarettes instead of one, sings hymns heartily into the morning air as we take our leave.

Memphis follows, where a well-designed museum experience at the Lorraine Motel, the site of Martin Luther King, Jr’s assassination, takes us slowly and with exquisite detail through the rise of the civil rights movement and culminates starkly in the rooms where MLK was transformed from leader to martyr for the cause. The National Civil Rights Museum is a deeply powerful place, with the time and space given to the shooting itself well-separated from the main site, which focuses on the long and arduous path of the proverbial movement, and features the voices and artifacts of that path adeptly and powerfully. But it is the small moments and discoveries that stand out, in the end: the low-placed photographs, almost an afterthought, that show the white mother of five who gave her life to the march from Selma to Montgomery, shot in her car for her role in ferrying march participants through a political bottleneck that allowed only 300 marchers through a long stretch of the narrow highway; the second-paragraph text that, in showing how a careful and methodical use of non-violent tactics among police and government in one site along the path to rights and justice slowed down the charge towards equality in those areas, reminds us that the use of such strategies is neither evidence of righteousness, nor exclusive to the side of love.

I am struck, especially, by tensions between then and now: by the young black men that occupy the open stools alongside serious-faced mannequins at the sit-in exhibit, texting and playing games on their phones, seemingly oblivious to the ironic gravity of the moment; by the laughter of the young patrons who line up to catch a glimpse of the balcony, and speak through Mahalia Jackson’s powerful voice as they approach. Later, stark racial divisions among the staff at the Beale St. barbecue joint we visit on our way out of the city – the constant patter of the white waitstaff as they hop from table to table, the black men manhandling heavy platters of ribs and catfish in the open kitchen, and the Latino males that emerge infrequently from the back to check on and gather up dirty dishware – will resonate that much more deeply for our path to the table.

More sit-in statues in Nashville and Louisville, though mostly by accident; our final goal is really Cincinnati, where the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center will offer both a historical look at the emancipation and suffrage of slaves, women, Native Americans, and other populations and groups in the United States, and an exploration of the various ways in which these conditions still exist today in places around the globe, through sex trafficking, indentured servitude, and forced labor, all of which plague the universe, and demand our action and our attention. I take many photographs of text: The Gettysburg Address is on our reading list for next year, as is King’s Letter From Birmingham Jail; pairing these is no accident, and although I am wary of turning class into a “what I did on my summer vacation” slideshow, I am eager to consider how to make these texts, and the others we will engage in, deeply meaningful to my students through their relevance to their own shared world.

But not just yet. Now we are here: it is summer, and the grass grows high off the porch upon our return. Our homecoming finds us renewed in spirit and determination, but we know, too, that processing such an exploration of self and society properly takes time and contemplation.

For now, then: a soundtrack of song, covers all, that covers all, from the protest music of the continuing revolution to the more modern tracks of place and time that allude to the continuing struggle to be present, productive, and free.

May we be a people so bold, and so deliberate. And if peace is not to be ours in our lifetime, may we go to the mountaintop nevertheless, and do the good work that brings us ever closer to the promised land.

- Rebecca Loebe: Southern Man (orig. Neil Young) [2014]

- Jen Todd: Pride (In The Name Of Love) (orig. U2) [2004]

- Monica Richardson: Abraham, Martin and John (orig. Dion) [2011]

- Rhiannon Giddens: Birmingham Sunday (orig. Joan Baez) [2015]

- Eleanor McEvoy: Eve Of Destruction (orig. Barry McGuire) [2011]

- Emily Elbert: Keep On Pushing (orig. The Impressions) [2013]

- Matt and Cameron Hammon: Up To The Mountain (MLK Song) (orig. Patty Griffin) [2014]

- Courtney Marie Andrews & Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy: I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free (orig. Billy Taylor) [2017]

- Ray Benson & Mounir Troudi: A Simple Song of Freedom (orig. Tim Hardin) [2014]

- Tim O’Brien: Sail Away (orig. Randy Newman) [2006]

Always ad-free and artist-friendly, Cover Lay Down will celebrate its 10th anniversary on the web this September thanks to the music-makers, the promoters, and YOU. Want to help keep CLD alive and streaming? Donate here and receive a very special mix of our favorite unblogged and exclusive coverage from 2015-2016!

Category: Mixtapes, Vacation Coverfolk One comment »

January 18th, 2020 at 5:26 pm

[…] separates the American South and North. I’m especially proud of the long essay that captures our 2017 journey, which I posted upon our return alongside a short soundtrack of social justice songs of hope and […]